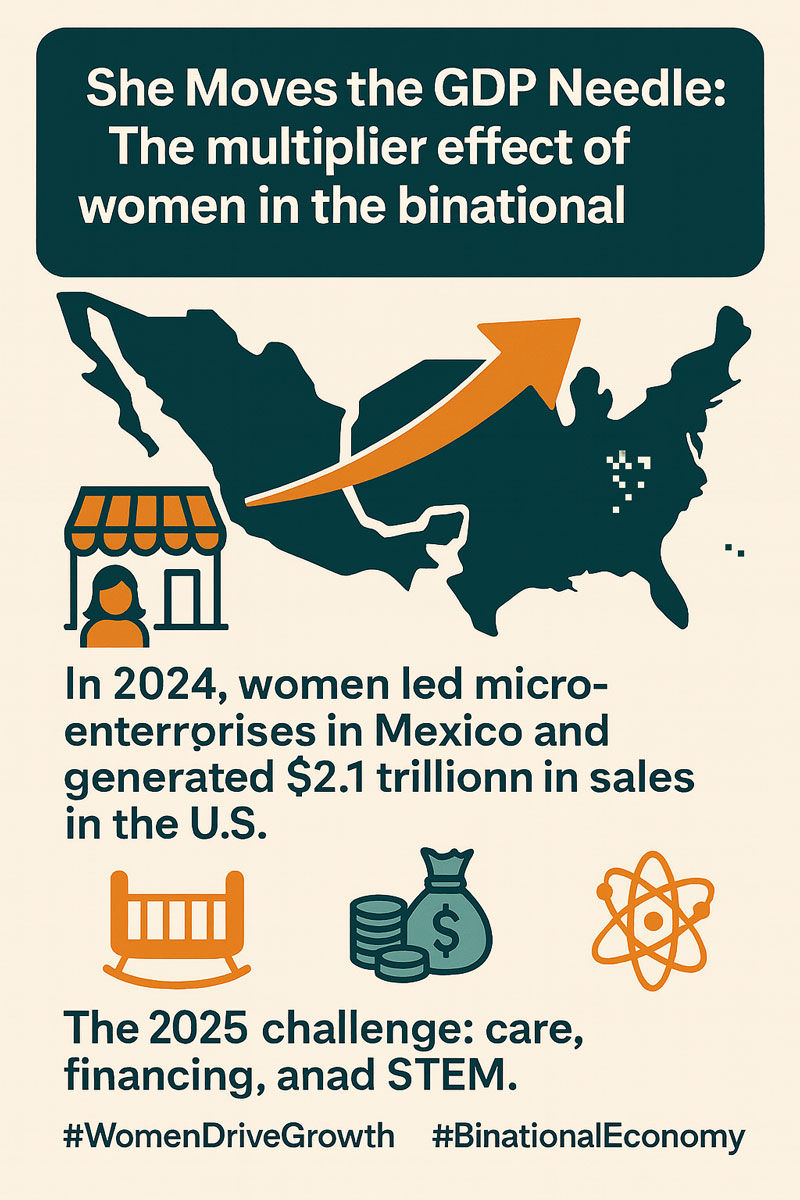

She moves the GDP needle. The multiplier effect of women in the binational economy

- Editorial

- Aug 21, 2025

- 3 min read

The evidence is clear: where women make decisions—in companies, supply chains, and local governments—there is more growth, more jobs, and greater resilience. In the United States, women-owned firms already generate $2.1 trillion in sales and employ 11.4 million people. They represent nearly 39% of all businesses when nonemployer firms are included, an expanding base that is redefining the local economies of mid-sized cities and metropolitan areas.

Female entrepreneurial dynamism rises from the bottom up. In 2024, the Small Business Administration’s Women’s Business Centers (WBCs) and state partners reported double-digit growth in advisory and training services, while the SBA itself recorded $56 billion in guaranteed financing—with 15,500 loans worth $5.6 billion directed to women-owned businesses. The impact is visible in neighborhood commerce, light manufacturing, and digital services, sectors where women are gaining market share.

In Mexico, female labor force participation is the latent engine of local development. In 2024, women’s economic participation reached 46.7% according to INEGI, while the OECD estimated 51.7% under its methodology for the first quarter of that year. Both figures represent progress compared to 2019, but they also highlight a persistent gap with OECD standards. At the same time, women already make up the majority of employed personnel in microenterprises (50.5%), the very business layer that sustains local employment and municipal revenues.

Public policies and support instruments explain part of this progress. “Mujer Exporta MX”—a platform run by Mexico’s Ministry of Economy—consolidated its fifth edition in 2024 with training programs and business matchmaking for women-led MSMEs, connecting them with buyers across the hemisphere. Meanwhile, Nacional Financiera strengthened programs offering technical assistance and training tailored to female entrepreneurs, and Mexican consular networks promoted entrepreneurship abroad through mentorship and business plan development. These are low-cost, high-impact policies that formalize, scale, and open new markets.

On the U.S. side, the support architecture combines capital and advisory services. The SBA and the National Women’s Business Council have recommended expanding the WBC network, opening more government procurement data, and closing STEM participation gaps. Niche banking—such as First Women’s Bank—and local funds have begun tackling the credit differentials that for decades constrained the growth of women-led firms. The result is more public contracts, deeper digitalization, and better integration into regional value chains.

Yet bottlenecks remain, and they are costing municipalities and states valuable GDP points. The most obvious is the care system. CEPAL estimates that investing around 4.7% of GDP in care services could raise female labor force participation by 12%, a jump with multiplier effects on productivity, consumption, and local tax collection. For municipalities seeking to attract nearshoring, industrial parks, or service clusters, expanding daycare capacity, professionalizing caregivers, and promoting shared household responsibilities should be seen as economic policy, not merely a “social issue.”

Financing is the second major challenge. Even with record loan disbursements, the cost of capital and risk aversion continue to penalize women-owned businesses—especially those innovating in advanced manufacturing, applied AI, and green solutions. National reports show that female entrepreneurship has grown faster than male entrepreneurship since 2021, but it still faces investment gaps that force many women to rely on personal debt instead of equity capital, a burden that limits scaling and technology adoption.

The third front is technology and data. Women entrepreneurs already lead in digital businesses, e-commerce, and knowledge-based services. However, the lack of interoperability in supplier catalogs and the limited availability of open procurement data restrict access to public contracts. In 2024 and so far in 2025, multiple U.S. and Mexican agencies expanded digital training programs for SMEs. The next step is to standardize supplier profiles, publish performance records, and use AI to match women-led businesses with the real needs of municipalities and states—from urban maintenance to cybersecurity.

What lies ahead for 2025? First, institutionalize care systems as basic economic infrastructure, with municipal metrics on coverage and quality. Second, scale productive credit with countercyclical guarantees and public monitoring of effective lending rates by gender, replicating innovations in niche banking and aligning them with state development funds. Third, leverage government procurement as a growth lever by setting participation targets for local women suppliers in subnational contracts, ensuring integrity and competition. Fourth, close the STEM gap with scholarships linked to binational value chains (aerospace, semiconductors, water management, and waste) with WBCs and NAFIN as territorial operators. None of this is philanthropy—it is a growth strategy. The results already visible in 2024 prove that, if designed well, these policies can turn the Mexico–United States region into a global laboratory for inclusive development.

Written by: Editorial

Comments